Bedford Park

“Bedford Park makes a lovely addition to the library of Asian American stories that interrogate our complicated histories in this country.”

Title: Bedford Park (2026)

Director: Stephanie Ahn 👩🏻🇺🇸

Writer: Stephanie Ahn 👩🏻🇺🇸

Reviewed by Li 👩🏻🇺🇸

—MILD SPOILERS AHEAD—

Technical: 3.25/5

Cinema is no stranger to East Asian stories of immigrant and generational trauma. It’s been told through splashy, award-winning fare like Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), the kid-friendly Pixar movie Turning Red (2022), and indie examinations like this year’s Korean Canadian film The Mother and the Bear (2026), among many others.

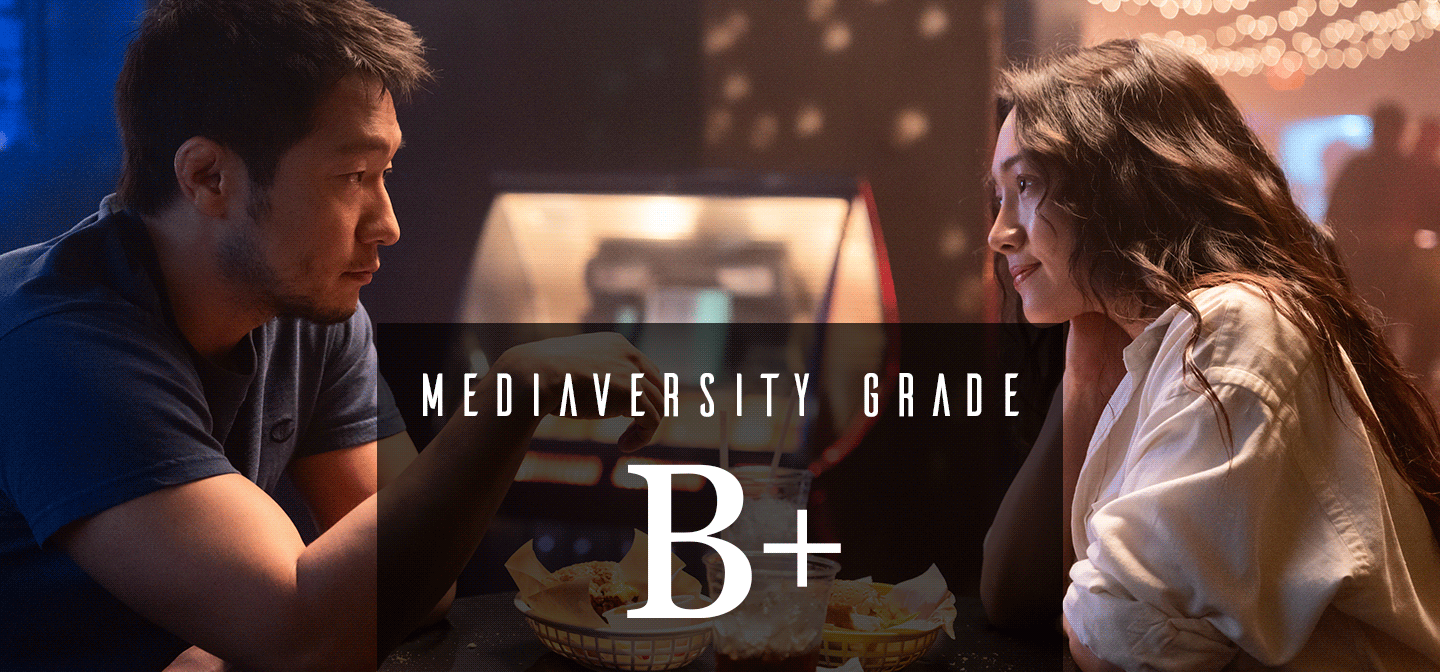

Written and directed by Brooklyn-based Stephanie Ahn, ruminative drama Bedford Park joins the ranks. Premiering at Sundance Film Festival today, the mournful New Jersey-set story follows two Korean Americans in their thirties, Audrey (Moon Choi) and Eli (Son Suk-ku), both stuck in patterns of behavior that aren’t working for them anymore. Whether it’s Audrey struggling to stand up to her parents’ expectations, or Eli running from his toxic adoptive family, this isn’t always an easy watch. But real life isn’t easy, and Ahn reflects that with open-eyed vulnerability.

Intimate cinematography lends a voyeuristic feel, with the handheld camera serving as a third-party observer of Audrey and Eli’s halting conversations as the two slowly open up to each other. Paired with fluorescent lighting from a sallow bulb in Eli’s threadbare kitchen, or from overbright lights in the mall where he works security, Bedford Park has an unvarnished feeling that borders on grim. Its characters are hanging on by a thread.

Bedford Park isn’t an escapist fantasy, but it does feel like a friend that commiserates with you, saying, “Hey, I’ve been there.” With a tentatively hopeful ending, Ahn suggests that breaking the cycle of family trauma is possible.

Gender: 4.25/5

Does it pass the Bechdel Test? YES

Bedford Park centers on the budding romance between Audrey and Eli, but the film prioritizes Audrey’s perspective. Importantly, it doesn’t shy away from things that affect women’s lives. Audrey experiences fertility issues and has a heartbreaking miscarriage, shown with the mundanity that accompanies pregnancy loss in real life. (She begins cramping and bleeding at a stranger’s house, checking herself into the hospital while the pain is still happening. Afterwards, she has to pretend everything is normal for the sake of her volatile dad’s comfort.)

In the background, Audrey’s contentious relationship with her mom ebbs and flows. They have a hard time understanding each other and often resort to yelling hurtful things. But in the end, Audrey’s mom demonstrates a willingness to try to hear her daughter’s side. When Audrey breaks down at the gesture and allows herself to be comforted by her mother, the love between them is clear.

Race: 5/5

With a Korean American filmmaker behind the camera, Bedford Park casts Koreans in key roles: Audrey and Eli, Audrey’s parents (Kim Eung-soo and Won Mi-kyung), and Audrey’s brother, Henry (Aaron Yoo). Eli also lives in a diverse New Jersey neighborhood, and multiple scenes include his Black neighbor Marvin and a Latina neighbor, both of whom speak a mix of Spanish and English. It’s positive to see a multi-ethnic community getting along, especially when much of traditional (read: white) media tries to pit communities of color against one another.

Korean themes are woven into other narratives, such as Eli’s transnational adoption into a white family—a relic of the Korean War. Ahn also explores cultural conflict between immigrant parents and their American children. More than once, Audrey’s parents angrily accuse her and Eli of being too “American,” as if no worse crime could exist. Racism is laid bare repeatedly, such as in a flashback when a Korean-born child asks his neighbors, Audrey and Henry, curiously, “What does ‘stupid chink motherfucker’ mean?” And at its most potent, Audrey wonders aloud about “han,” describing the word to Eli as a Korean concept of heartache when a person carries their family’s trauma—a clear echo of Bedford Park’s portrayals of intergenerational pain.

Bonus for Disability: +0.25

Disability is a minor but normalized part of this film. Ex-wrestler Eli has cauliflower ear and burn scars on his back from a traumatic childhood incident, and Audrey’s father uses a cane as a mobility aid.

In addition, Eli’s neighbor Marvin uses a wheelchair. When Eli and Audrey drive past Marvin on the sidewalk, they give him a lift. Audrey—who’s a physical therapist—guesses that Marvin has osteoarthritis in his knee and recommends physical therapy rather than his continued steroid shots, offering a nice peek into the specificity of disability without using it to define Marvin’s character.

Bonus for LGBTQ: +0.25

While he has just one scene with Audrey on screen, Henry reveals that he’s in a serious relationship with a white man. He talks about needing to finally tell their parents, and it’s positive that the movie includes a queer character of color, even if only in a minor role.

Mediaversity Grade: B+ 4.33/5

With a female perspective and strong explorations of what it means to be both Korean and American, Bedford Park makes a lovely addition to the library of Asian American stories that interrogate our complicated histories in this country.