The Woman King

“The Woman King provides a template for how men can advocate for women.”

Title: The Woman King (2022)

Director: Gina Prince-Bythewood 👩🏽🇺🇸

Writers: Dana Stevens 👩🏼🇺🇸 and Maria Bello 👩🏼🇺🇸

Reviewed by Carolyn Hinds 👩🏾🇧🇧🇨🇦♿️

Technical: 5/5

There’s beauty in strength—in the strength of Black women fighting for their king, each other, and for their home. There’s beauty in the scars borne from wars, including the wars fought within us, because while not all scars are visible, they’re deep and lasting, and they can be survived. In director Gina Prince-Bythewood’s latest film The Woman King, a regiment of Black women warriors known as the Agojie encompass all these traits in fearsome fashion as they battle to protect the kingdom of Dahomey (modern day Benin).

As an action film, The Woman King has everything a fan of the genre could want. Fight choreographer Jénel Stevens, who starred as one of the famed Dora Milaje in 2018’s Black Panther, and stunt coordinator Daniel Hernandez, who worked with Prince-Bythewood on her previous film The Old Guard (2020), create pulse-pounding sequences that impress yet more when you realize they’re based on reality. Just as the historical Agojie clashed with male warriors from neighboring African tribes and French battalions, women duke it out with men twice their size in this film. It’s unlike anything we’ve seen to date in Western cinema, but it isn’t perfect; the camera can hug too closely at times, attempting to create intimacy with its characters but simply making it difficult to follow. (Coincidentally, this is an issue I also had with The Old Guard.)

Still, the world-building is indisputable. Cinematographer Polly Morgan and special effects supervisor (and Oscar winner) Sara Bennett do a terrific job translating the beautiful vistas of West African topography and Dahomey landmarks before the ravages of slavery and European colonization. And the lovely score by musician Terence Blanchard features music of Benin and West African culture, swelling with intense beating drums and woodwind instruments, yet receding for quieter moments of reflection by characters. Renowned singers like Dianne Reeves and Tesia Kwarteng, as well as South African and Grammy winner Lebo M, who composed soundtracks for the Lion King films, were brought on to give powerful voice to emotional scenes.

As much as the action and music make up a driving force of the film, it’s the performances by lead cast members like Viola Davis as the respected General Nanisca, Lashana Lynch as fearless soldier Izogie, and Thuso Mbedu who plays their new recruit, Nawi, that ensure there’s just as much heart to this story as there is grit.

Gender: 5/5

Does it pass the Bechdel Test? YES

Prince-Bythewood’s film demonstrates how strong Black women had to be then (and have to be now). The leads mentioned above each showcase unique identities and resilience, as do supporting characters of spiritual mentor Amenza (Sheila Atim) and Nawi’s fellow recruits, Fumbe (Masali Baduza) and Ode (Adrienne Warren). Between so many women, a wide range of relationships and topics of conversation can take place.

There’s no doubt that storied actor Davis has the ability to command a roomful of characters. But on top of being physically imposing, aided by the months she and the cast spent training for their roles, she’s crucially given the chance to be soft and feminine as well. Nanisca is both a leader and a friend to Amenza, whose spiritual counsel she weighs and balances with her own beliefs. As for Atim, her previous projects like Bruised (2021) have given her ample practice to exhibit vulnerability and toughness. She does it again here, but layered with some of the film’s more humorous moments.

Mbedu and Lynch play two sides of the same coin, their characters Nawi and Izogie subtly mirroring each other as they reveal painful pasts (and both blossom into incredible fighters). In a scene where Izogie cornrows Nawi’s hair—a moment that will especially resonate for Black girls and women—she advises Nawi not to let her burgeoning feelings for a Portuguese man weaken her.

I’d be remiss not to mention the film’s central relationship between Nanisca and Nawi. It begins prickly, as the Agojie general attempts to keep her reckless young recruit in line. But over the course of the film, reconciliation and catharsis mounts into some of The Woman King’s most effective scenes.

These bonds of sisterhood are what makes this film so special. Furthermore, this focus on female warriors isn’t at the expense of other characters. (If only we could say the same for the vast majority of war stories, which almost seem to take pleasure in sidelining women and girls.) For starters, the title of the film comes from the real King Ghezo—played charmingly by John Boyega—who advocated for establishing a “Woman King,” or Kpojito. In the film, Boyega’s Ghezo serves as an important ally to Nanisca, demanding that she be treated as an equal to him in power and standing.

Through his example, the film provides a template for how men can advocate for women. Ghezo uses his political power to adjust society and its rigid ideas of gender roles so that the entire kingdom may benefit from the talents of the Agojie. In a real-world reflection, Boyega himself has been a staunch supporter of Black women, calling out Hollywood’s tendency to ignore dark-skinned Black women in particular. He brings full circle the empowered message The Woman King carries about the responsibility of men to fight for gender equality.

Race: 5/5

Dark-skinned Black women of different sizes, heights, with natural hair, wearing traditional West African clothes, singing traditional music, dancing, fighting, laughing, crying, throwing shade and showing respect … this is what true representation is about! It’s about seeing ourselves as heroes and villains. Being messy and redeemable. Being complicated and relatable.

Prince-Bythewood’s direction succeeds so well on this front, that it may come as a surprise to learn that The Woman King was created and written by two white women. Dana Stevens and Maria Bello came up with the idea for the film after visiting Benin in 2015, and they put in the work, avoiding many of the stereotypes that befall Black actors and their onscreen characters. Stevens and Bello show what’s possible when white creatives who want to write stories about Black people actually respect our perspectives and collaborate with us.

For instance, historian Leonard Wantchekon—who is a direct descendant of an Agojie warrior—had an integral role in helping the filmmakers navigate what could have been a major sticking point. Before The Woman King’s world premiere at Toronto International Film Festival, there were concerns on social media that the film would ignore Dahomey’s involvement in the slave trade. And to be sure, some moviegoers still maintain that the film sanitizes an uglier history. But at the very least, The Woman King directly addresses Dahomey’s moral quandary by placing it at the heart of the plot.

In my view, the film successfully portrays the reality of Black Africans playing a part in the tragic commodification of human beings, yet does so without falsely equating it with the culpability of white Europeans and Americans, who fashioned entire economies around chattel slavery. Unlike so many Hollywood films that are content to paint slavery as something cartoonishly evil that happened once in the United States and then went away, The Woman King argues that African nations like Dahomey may have participated in the trade of enslaved people, but they were under financial and military oppression by colonizers and had very few means of gaining enough independent wealth to survive without it. The film brings shades of gray to a narrative that is so often oversimplified.

Bonus for Age: +0.75

In the span of two years we’ve had multiple films showing women in their 40s and 50s kicking ass: Gunpowder Milkshake (2021), Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), Bruised, and now The Woman King. It’s a trend I hope continues.

With her casting of Davis (57 at the time of this review), as well as women like Charlize Theron (47) in The Old Guard, Prince-Bythewood has provided multiple examples that other directors and writers should follow by not using age, race, or gender as limiting factors when considering who can be and should be an action hero.

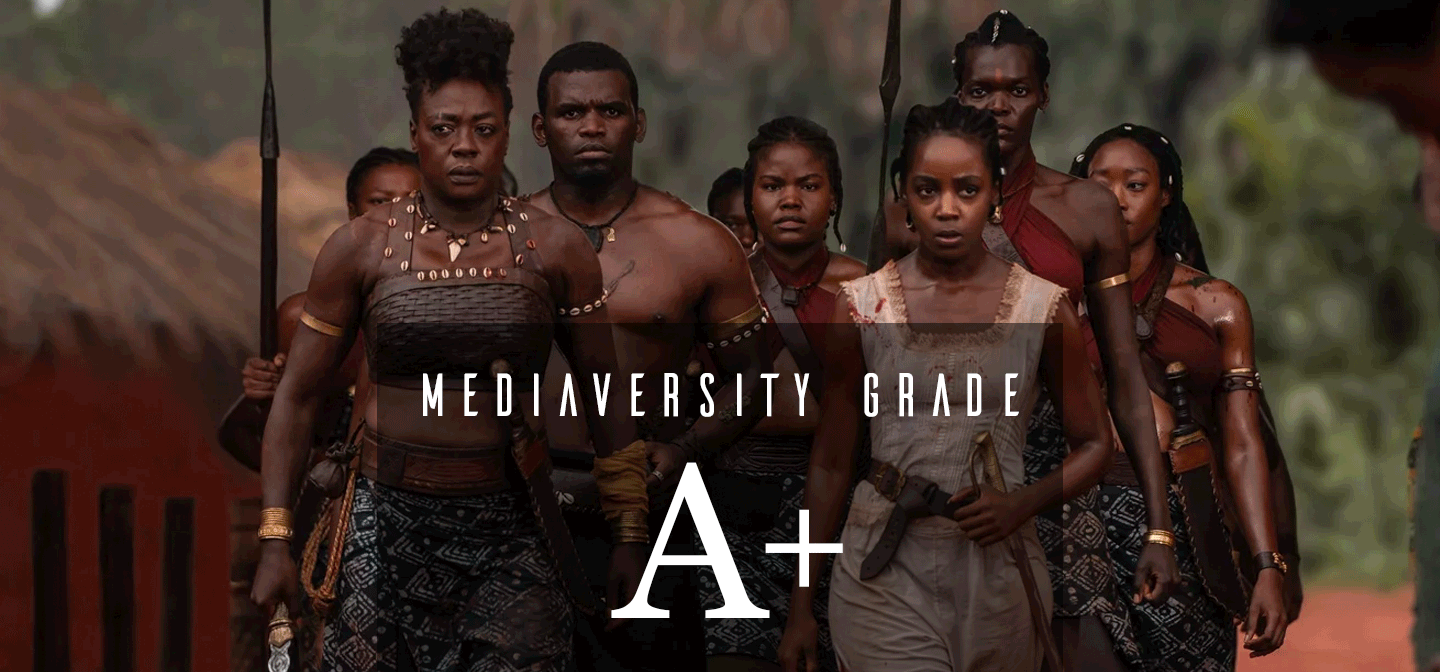

Mediaversity Grade: A+ 5.25/5

Not only is The Woman King directed by a Black woman, nearly all of the film’s departments are helmed by female creatives. Their lived experiences translate perfectly into a movie that showcases empowerment without minimizing the pain and suffering that so many have had to bear throughout history.

It’s been amazing to see the excited reactions from Black women who finally have heroes we can relate to on every level. In The Woman King, we get to see ourselves represented as fighters, leaders, and liberators. I can only hope this isn’t the end; history is full of inspiration, after all, like Queen Nzinga of Ndongo who fended off the Portuguese and protected her nation against enslavement. Make us another The Woman King (or ten), and I’ll be there bright-eyed and bushy-tailed.